The Limits of Principle: Who Lives and What Dies

In the 1950s, nations rejoiced when children stricken with polio who otherwise would have died were saved by the then new "iron lung." Throughout the decade, magazines and newspapers detailed the life triumphs of those persons as they lived full if physically restricted lives. By the 1990s, however, advances in medicine were met with a change in ethics. Saving lives became less important than guaranteeing "quality of life." Lives restricted by physical or cognitive differences were increasingly assumed to be unworthy. Increasingly, to save people to a physically restricted life was seen by many as a failure.

In the 1950s, nations rejoiced when children stricken with polio who otherwise would have died were saved by the then new "iron lung." Throughout the decade, magazines and newspapers detailed the life triumphs of those persons as they lived full if physically restricted lives. By the 1990s, however, advances in medicine were met with a change in ethics. Saving lives became less important than guaranteeing "quality of life." Lives restricted by physical or cognitive differences were increasingly assumed to be unworthy. Increasingly, to save people to a physically restricted life was seen by many as a failure.

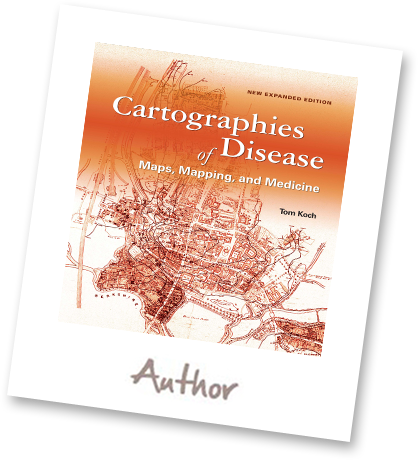

The Limits of Principle considers this change in our ethics, one in which a belief in the "sanctity of life" was redrawn to a circle of "protected life qualities." It was no longer "who lives, who dies," but who was protected and what was not. During this period the debate ranged over issues of abortion and fetal choice (Down syndrome, anencephaly, hydrocephaly, etc.), eugenics, euthanasia and assisted suicide.

Hospitals have struggled to adapt, transforming a changing ethic into ethical policy and practice. In the realm of organ transplantation, should a person with Down syndrome be equally eligible, or not? Is a criminal incarcerated for a crime as eligible as a normal citizen for a transplant? As a research associate in bioethics, Tom Koch considered these questions, and the limits of the principles that inform the problem, at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada. Innovatively, his work involved focus groups with both normal citizens and hospital officials in an attempt to answer not simply the problem of organ distribution, but more generally the ethics of our relations with persons of difference in society.

From Book News, Inc.

As a specialist on care giving for the elderly, Koch birthed this extension of his thinking on ethical issues to both ends of the developmental scale at the 1995 International Conference on Bioethics. Contending that the conundrums raised by modern medicine's ability to prolong life and the scarcity of organs for transplants require that we venture beyond the "clash of absolutes" of 18th century ethics, he applies an Analytic Hierarchy Process to a multicriterion decision-making continuum rather than an either/or resource perspective. Distributed in the US by Greenwood. Book News, Inc.(r), Portland, OR.

From Amazon.com: Reader Reviews:

"A superb book for people facing tough medical ethics issues," April 27, 1999.

This is a superb book for nurses, doctors, social workers and family members wrestling with difficult medical ethical questions. Who should go first in the lineup to receive a heart transplant: a young child or a father of three? Should a person with Down's syndrome be equal to others? How about a convicted criminal? Or someone age 75? Tom Koch explores these difficult questions and then offers a framework for health care workers and others to help work through their own answers. He examines what it means to be human and the sanctity of human life -- and how a better historical understanding of these concepts and a reasoned methodology can help guide us as we make difficult life and death choices today. Koch does an excellent job of weaving the practical and human with the technical and philosophical. This is a must for those who are forced to make the choice of who lives, and who dies.